Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier Volume 3 (1) Winter 2015 Kimberlee Gillis-Bridges University of Washington

Why Hybrid Pedagogy?

Since 1996, my web-enhanced courses have supplemented face-to-face instruction with course websites and online film or reading responses. I’ve also used online tools to support multimodal projects like analytical web sites and clip annotations. Over the past two years, however, I’ve experimented with hybrid instruction in my cinema studies courses, replacing face-to-face meetings with online activities (see Mayadas and Miller 2014 and University of Wisconsin 2014 for definitions of web-enhanced and hybrid instruction). In what follows, I will focus on two iterations of an upper-division women filmmakers course at University of Washington: one taught in spring quarter of 2013 and the other in spring of 2014. Both enrolled junior and seniors, a majority of them English, Cinema Studies, or Cinemedia majors and a minority from social science or science disciplines. In discussing the courses themselves and curricular revisions I made to both versions, I will address assignment design and argue for systematic assessment of teaching methodologies.

I introduced hybrid instruction in 2013 to more effectively incorporate films screened at the Seattle International Film Festival (SIFF) into the curriculum. Since 2008, my students have attended SIFF, viewing one common film and choosing two others from a menu of four to five offerings determined via class vote. Although students who took the course between 2008 and 2012 found the festival environment energizing, some struggled to negotiate work and screening schedules. Their class workload also increased. Because the SIFF calendar does not appear until midway through the quarter and screening dates for selected films typically do not coincide with the class meeting schedule, I required students to add SIFF film attendance to existing class screenings, discussions, and readings. Moreover, I compressed discussion of SIFF films into one or two class periods, effectively diminishing opportunities for in-depth analysis. A response prompt from my 2012 American independent film course encapsulates the problem while attempting to mitigate its effects: “Since we have limited class time and many films to cover, you may respond in detail to one of your classmates’ postings.” By moving to hybrid instruction, I hoped to give students flexibility to attend SIFF screenings that overlapped scheduled class meeting times and to pay greater analytical attention to the films themselves.

From Web-Enhanced to Hybrid Course Design

My 2013 course, which enrolled 12 students, and my 2014 course, which enrolled 37, represent two models for hybrid course design. In 2013, students met face to face for seven weeks and interacted exclusively online during the three weeks they attended SIFF. In 2014, the festival attendance weeks featured one face-to-face discussion and several online interactions. Whether online or mixed mode, my course design maintained a principle central to my web-enhanced courses: that online activities have a clear connection to face-to-face activities as well as course learning goals. My hybrid design also included complex tasks divided into scaffolded activities; prompts that require students to apply course readings to specific film shots, scenes or patterns; supplementary media; interactivity; and clear grading criteria. During weeks my classes met solely face-to-face, they completed assignments using platforms they would employ more extensively when meeting online. I could thus provide necessary technical instruction and troubleshoot problems before they became learning obstacles during online instruction weeks.

In both 2013 and 2014, students used Canvas’s discussion feature during the first seven weeks of the course to post 250- to 300-word responses to questions I posed on course films and readings (see Figure 1). Students submitted these weekly responses before class. Their postings allowed me to refine my teaching agenda. I could ask students to expand upon their response claims during class discussion, place them into small groups with peers who had selected the same question, or arrange debates among students whose ideas supplemented and challenged one another’s. Furthermore, I could revise prepared short lectures to address issues students didn’t fully comprehend in their responses.

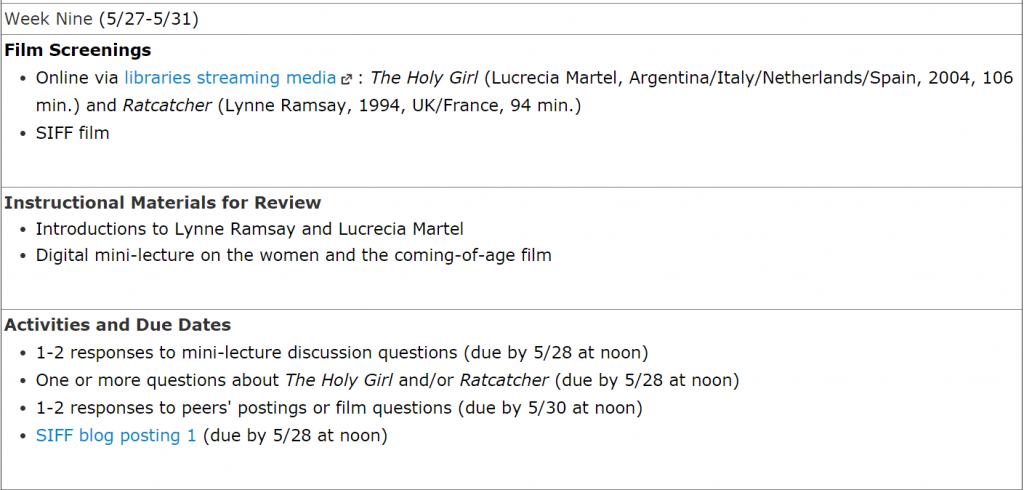

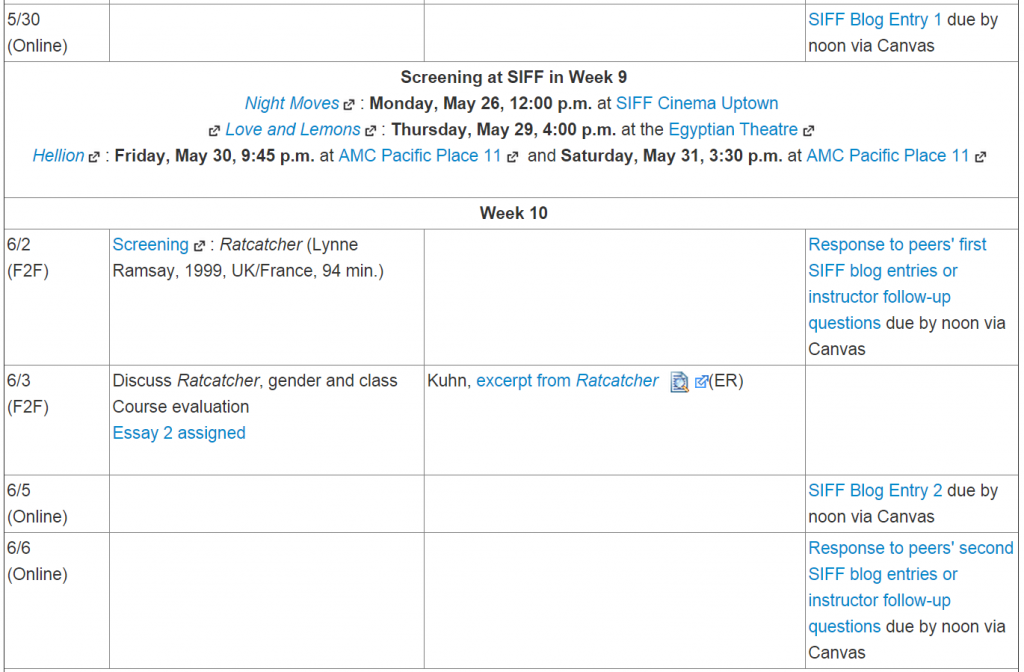

Students submitted these weekly responses, which I graded on a credit/no credit basis, before class. When students in the 2013 class shifted to solely online instruction, they used the same discussion tool to answer one of my questions about each week’s assigned course film[s] (see Figure 2), respond to peers’ ideas or my follow-up questions (see Figure 3), and to compose and comment upon SIFF film blogs (see Figures 4 and 5). The discussion platform allowed me to incorporate screenshots as well as film clips I created with Handbrake directly into assignment prompts. Students could likewise embed images and video into their postings. Students received full, partial, or no credit for their work, with points assigned for tasks completed.

In addition to using the discussion area, I continued to use Prezi for lectures on course filmmakers and films. During weeks students met online, I used Audacity to record commentary that I added as voiceover to select Prezi slides. Not only did I chunk my remarks into two- to three-minute segments—a practice that accommodates current attention spans and simplifies later revision—but I also limited my lectures to thirty minutes maximum. Moreover, I linked lectures to online discussion by highlighting elements for students to analyze as they watched the assigned film online and composing discussion prompts focused on elements outlined in my lecture (see Figure 6 below and Figure 2 above).

In 2014, students listened to my lectures and discussed assigned films face-to-face. They used the online discussion area to compose blog entries on SIFF films and respond to their peers’ ideas, questions, or follow-up questions I posed (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Excerpt from student SIFF blog entry on Hellion, peer and instructor responses, and student’s response to both peer and instructor, Spring 2014.

My 2013 and 2014 course calendars outline the assignment sequences discussed above (see Figures 8 and 9). They also demonstrate the connections I attempted to make between discrete online activities and between face-to-face and online instruction. For example, in 2013, online lectures prepared students for screenings and film responses. Screenshots and video clips embedded into discussion prompts allowed students to review key sequences as they composed their analyses and commented on their peers’ ideas. In 2014, students continued to address peers’ online questions and responses to their SIFF blogs during face-to-face meetings. In both 2013 and 2014, the SIFF blog assignment included the option to compare assigned course films to the SIFF film discussed in the entry. Students were also encouraged to develop a blog entry into a longer final essay for the course.

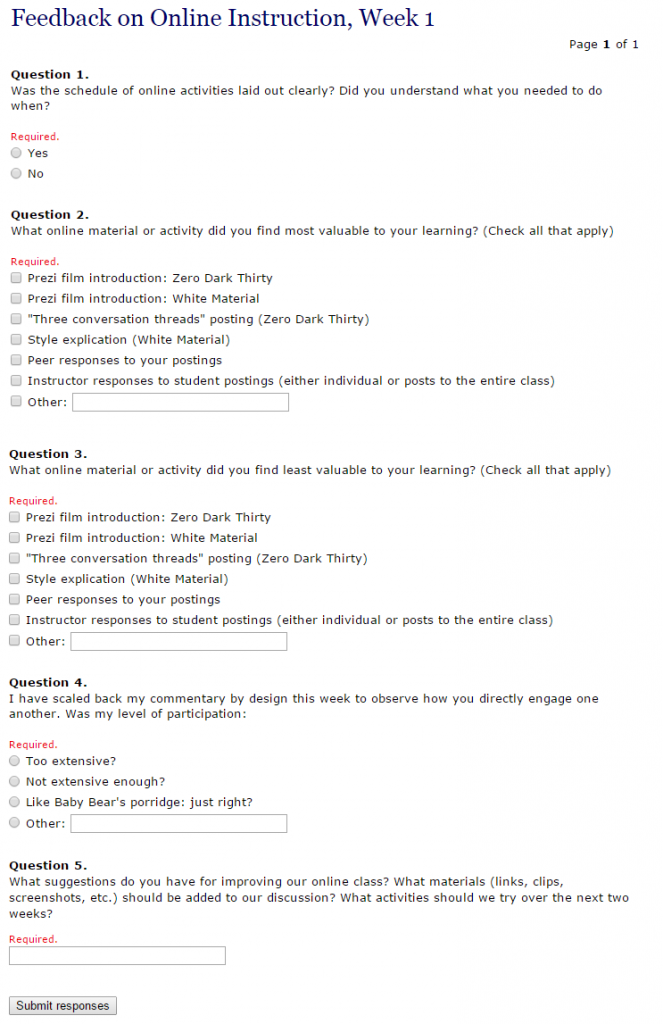

Assessment, Or, What to Do with a Course and a Half

In addition to highlighting assignment sequences, my course calendars also show curriculum revision. During the first week of online instruction in 2013, my course became a course and a half. So greatly did I fear students dismissing online activities as easy or feeling less accountable for their work that I assigned far too much: two online class screenings (with accompanying lectures, film responses, and replies to peer analyses) as well as a SIFF film screening, blog entry, and response to selected peers’ blog entries. I was overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material students seemed rushed to produce and scrambled to respond to their work. Fortunately, my course design included an anonymous student survey distributed after the first week of online instruction (see Figure 10). Survey data confirmed that the workload was not only unreasonable, but also prohibited sustained intellectual engagement with films and readings. Consequently, I altered the schedule to one online film screening (with accompanying lecture, film response, and reply to a peer) and one SIFF film screening, blog entry and peer response per week. I also shaped discussion prompts around open-ended topic threads and limited my online presence to commenting on connections among students’ ideas—survey responses identified both practices as valuable to learning.

My shift from exclusively online instruction in 2013 to blended instruction in 2014 represents a response to a 2013 end-of-quarter survey and to experiences learning from fellow members of a Faculty Technology Teaching Fellows Institute in summer 2013 and a faculty learning community focused on scholarship of teaching and learning in fall 2013. As a Technology Teaching Fellow, I redesigned a web-enhanced literature course for hybrid instruction. Data from student surveys and analysis of student work produced in hybrid and face-to-face versions of that course led me to reevaluate my plans for hybrid instruction in spring 2014 (see Angelo and Cross 1993, 105-114 for a discussion of assessment methods linked to teaching goals and McKinney 2007, 67-82 for an introduction to quantitative and qualitative analysis of teaching methodologies). I determined that I need not omit face-to-face meetings altogether to accommodate SIFF screenings, blog composition, and peer response. However, I wanted to maintain the nearly one hundred percent participation rate encouraged by online posting and response, as students had cited heterogeneity of perspectives as beneficial to their learning. Consequently, I decided to discuss assigned films face-to-face and let students take the lead on analyzing and responding to each other’s analyses of SIFF films online.

Future Plans

Replacing some face-to-face meetings with online activities, particularly those focused on SIFF films, fulfilled my goal of incorporating festival films more fully into my curriculum. In my web-enhanced 2012 course, where students composed a single response to SIFF films, only 23% analyzed a SIFF film in their final course essays. Forty-two percent did so in my 2013 hybrid course, and 71% composed their final essays on SIFF films in 2014. I’ve consequently altered the course topic to film adaptation, a subject that should offer opportunities to compare assigned and festival film adaptations of the same text. While I’ve yet to finalize the course design, I know I will continue to couple my development of online and hybrid curriculum with assessment that both supplements institutional evaluations and goes beyond a general sense that students are producing better or worse work when I alter my pedagogy.

Works Cited

Angelo, Thomas and K. Patricia Cross. 1993. Classroom Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Teachers. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mayadas, Frank and Gary E. Miller. 2014. “Definitions of E-Learning Courses and Programs, Version 1.1, Developed for Discussion within the Online Learning Community.” Online Learning Consortium eLearning Landscape, September 18. http://onlinelearningconsortium.org/updated-e-learning-definitions/

McKinney, Kathleen. 2007. Enhancing Learning Through the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning: The Challenges and Joys of Juggling. San Francisco: Ankar Publishing.

University of Wisconsin Learning Technology Center. 2015. “About Hybrid: Frequently Asked Questions.” Accessed January 15. http://www4.uwm.edu/ltc/hybrid/about_hybrid/index.cfm