Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier Volume 3 (1) Winter 2015 Kelly Kessler DePaul University

The beginning of my appointment at DePaul University directly coincided with The College of Communication’s (my home unit’s) push to increase its profile as a site for online learning. Lucky enough to be employed by a school with excellent faculty training in and faculty support for online learning, I have found the integration of the online and hybrid classroom into my roster of existing courses less bumpy than many. I am fortunate to have had skilled IT consultants and a digitization team who help with the nuts and bolts of making these classes happen (e.g. digitizing content, troubleshooting technical issues, designing user-friendly sites that integrate my created content, etc.). This essentially freed me of the technical burden experienced by many who venture online, and instead left me to worry mainly about how best to convert my learning goals, content, and assignments into something amenable to an online forum. The shift to online learning presents instructors of the 21st century with new challenges regarding student-student and student-professor engagement. I would like to use this essay to share and explore interactive techniques, as well as pitfalls and rewards I have experienced in the online media classroom. Notably, one of the main challenges of teaching online is feeling like one is teaching in a vacuum; I hope this kind of dialogue between media instructors can help address that.

I began teaching online in 2009 with a hybrid (half online/half face-to-face) version of Media and Cultural Studies, an undergraduate course that serves as a form of toolbox for thinking critically about media. Each week students cover a critical lens such as ideology, semiotics, political economy, or identity politics. I had struggled with students’ unwillingness to read and the resultant dearth of deep discussion or application in past face-to-face sections of this course, and I used this change in modality to address this issue. Ultimately, the half-shift in modality and the major online component integrated into the course brought an immediate increase in student participation and comprehension. Through small group wikis, students engaged with weekly readings, popular media, and each other and then brought their writings back into the face-to-face classroom.

Students were placed into groups of four, with rotating weekly assignments to be completed on their PBworks wiki sites. One would post a piece of media—from YouTube or the like—and write a 100-word explanation as to why it should be used to discuss that week’s reading. The second member would then perform a 400-500 word close analysis of the peer-chosen clip using the week’s reading. The third person’s role was initially to reconceptualize the clip to better adhere to or refute the ideas of the reading, but students seemed to struggle with this. More recently, person number three—per student feedback—chooses another group’s wiki and performs a 400-500 word analysis of their chosen piece of media. Person number four has the week off. In addition, each week every student has to comment on some other group’s page, giving them further opportunity to see what has been going on with other groups.

In the beginning, this assignment had primarily been created as means to force students to read. Responses could not be posted late and because the wiki assignment was worth 30% of the overall quarter grade, students would be foolish to simply ignore the deadlines.[i] Because of the nature of the assignment, they had to engage with the reading material prior to classtime. In the end, this assignment accomplished much more than I had expected. First, it did encourage students to read beforehand and therefore fostered a much richer engagement with the concepts at hand during the face-to-face class. Second, it allowed students—in a pressure-free online environment—to see the kinds of work their peers were doing. Third and perhaps most importantly, the wiki assignment provided the students with a sense of agency and ownership within the classroom. Because each theoretical concept was discussed through their chosen media, it became their class and not just mine. Instead of discussing Laura Mulvey through Hitchcock and VonSternberg for the millionth time, the class engaged with her concepts through student-chosen clips such as Gossip Girl, Friday, and Die Another Day. I believe that using their choices in the face-to-face meetings gave students an additional buy-in to the course and what we were trying to accomplish there. It also automatically made the class more relevant to them, as the lectures and discussions were somewhat freed from what I thought was relevant and instead revolved around their interests.[ii]

Encouraged by the quality engagement in my hybrid class, I soon ventured into fully online territory. My most recent fully online course experiments with increased levels of student-student and student-instructor interaction in various ways. This History of Television and Radio course—an undergraduate elective, popular with both majors and non-majors who can use it as a liberal studies credit—blends more traditional forms of instruction (narrated PowerPoint lectures, online quizzes, and screenings) with more online-specific content like blogs, wikis, and synchronous online classrooms. Still a work in progress, this course both pushes levels of student interaction and forces me to be aware of the tipping point that pushes the course into overwhelming territory from both student and instructor perspectives.

Only one version of this last course has used synchronous or real-time activities. In its first incarnation I integrated synchronous small group meetings in hopes of fostering more dynamic interaction. Using the virtual interview client Scopia, I conducted several interviews with industry folks with whom I had previous relationships (e.g. actor Jack McBrayer, actor/producer Lennon Parham, writer/producer Elizabeth Klaviter) tailoring my questions directly to the course.

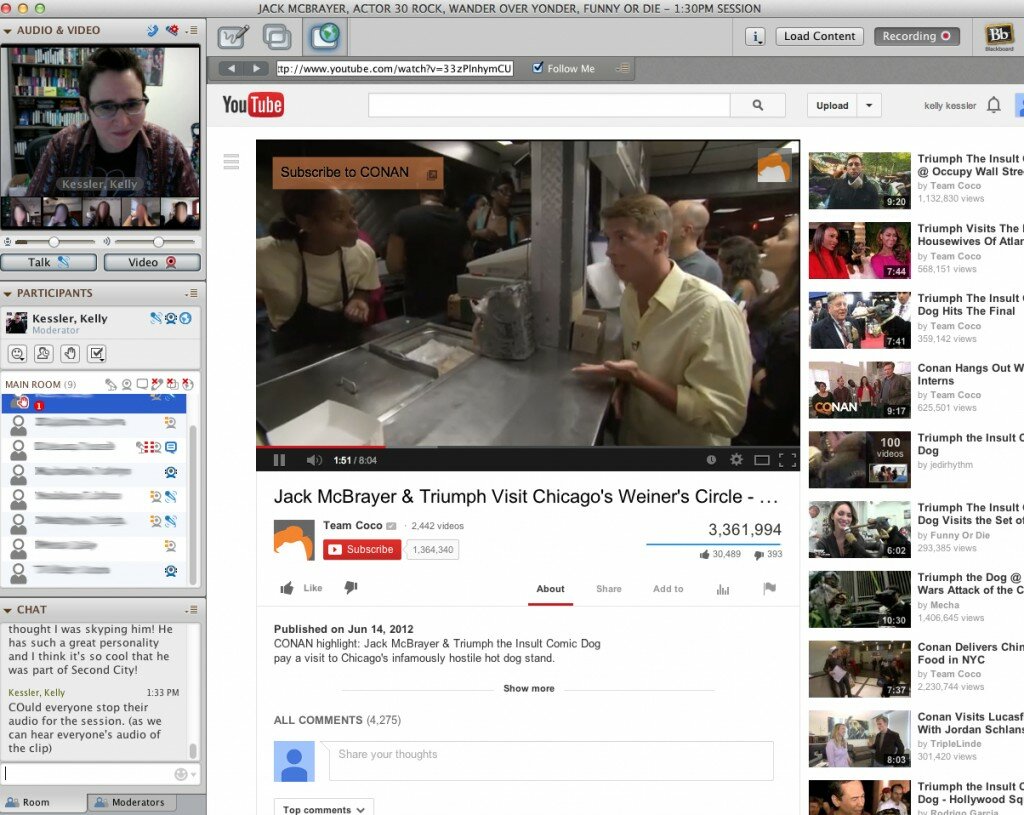

I directed students to watch an interview asynchronously and then meet in small groups virtually with me to discuss the interview’s relationship to the class, television history, and the current industrial landscape. On a practical level, this kind of real-time student-student and student-professor interaction required a complicated process of scheduling. I collected students’ seven-day schedules using when2meet.com and scheduled synchronous group meetings based around clusters of availability. In the end, the sessions proved quite useful. Using the interface Collaborate students could login from computers or mobile devices to participate via video. The interface allowed on-the-fly sharing of content from my computer and websites like YouTube for real-time viewing. Students could participate via video/audio, yes/no toggles, and a chat sidebar, encouraging some rich direct and parallel conversations to develop.

A sample screenshot of the Collaborate interface, illustrating the simultaneous video, website, and chat features.

All in all, this engagement method provided me with an excellent means to bring students together and foster a more dynamic discussion than many asynchronous methods offer.[iii]

For this class, students also build small group wikis around individual television seasons, using online resources, video, and period popular press sources to explore the interrelatedness of content and context. In another assignment, they create fictional bios and use period articles and large and small group discussion boards to debate early 20th century wireless development from various identity standpoints, exploring the period intersection of technology race, class, and gender. For extra credit students can participate in the class “Flat Sarnoff/Flat Farnsworth” blog that chronicles their visits to Chicago (or more distant) television landmarks with paper versions of the television icons. Augmenting these elements with personalized and up-to-date emails and video check-ins, the course design provides students increased and varied opportunities to engage directly with me, each other, and assorted (and at-times self-selected) content to an end of increased collegiality and intellectual collaboration.

The shift to online learning has been a tricky one at times. Although moving course content online can be technically arduous, attempting to maintain a productive and vibrant exchange of ideas akin to the face-to-face classroom can be doubly challenging. Professors no longer have a literally captive audience, making it necessary to find productive engagement through more innovative means. Although I in no way think I have mastered the modality, some of these techniques have led to some excellent discoveries on the parts of students and gratifying teaching experiences for me. Give students a reason to watch, listen, and engage. Personalization, variety, interactivity, and agency can help create a vibrant learning and teaching space, and hopefully one that doesn’t encourage your students to binge watch Breaking Bad while listening to the lectures.

At least weekly I upload on-the-fly videos in which I address recent assignments, setup and clarify the week’s assignments/goals, and sometimes wear thematic hats. Sometimes cats might appear. It gives a snapshot of who I am to students who never actually meet me in person.

To respect student privacy, please note that all links to assignments are to the sample sites I maintain and provide to the students as examples.

[i] I maintain my own wiki and post a weekly piece of media and associated 100-word explanation. If a students’ group member fails to post on the required day, s/he can use mine. This prevents students from being penalized for a group member’s failure to perform.

[ii] I have now integrated wikis into many of my face-to-face classes as an easy way to share and present individual or group work. PBworks also includes detailed input tracking, eliminating guesswork regarding which group members did what and when.

[iii] I am still tinkering with this assignment, as scheduling synchronous meetings proved a bit onerous for everyone. I am currently piloting a small group, asynchronous version of the assignment, as the interviews are an excellent resource and the interaction was incredibly valuable.