Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier- Critical Pedagogies in Neoliberal Times Vol. 3 (2)

- Holly Willis

- University of Southern California

The “pedagogical turn” in contemporary art has received significant attention in the context of participatory art practices – thanks to the work of Claire Bishop, Nato Thompson and Pablo Helguera, among others. However, not much has been written about the role new media artists play in creating alternative experiences for critical learning in an era characterized by the increasingly corporatized and neoliberal American university setting. One clear exception to this lack would be the work of Rita Raley in Tactical Media, an excellent chronicle of politically-motivated interventionist tactics by media artists. Similarly, Brian Goldfarb advocates powerfully for what he dubs “visual pedagogy” within informal learning contexts. While he offers a strong critique of the traditional bias against the visual in the context of learning, I believe media artists have more to offer in this context. As universities in an age of neo-liberalism grow increasingly entrepreneurial in spirit, speaking of “products,” “services,” and “customers,” as well as of “economies” and “global markets,” media artists oriented toward pedagogical practice reflect back what is lost in the entrepreneurial agenda, reminding us that our role within the university is to critically examine our values and to engage in public discourse.

Media artists are creating experiences through which participants engage in powerful forms of criticality, using media and interactivity to reflect on issues of power, infrastructure, consumerism, and the body as it becomes networked. This work rejects – or at the least problematizes – the spectacle associated with so much of the media presented on contemporary urban screens. It calls attention to the infrastructures of media and communication that enable the use of myriad devices, but which grow increasingly complex and invisible. Therefore, these forcers are not part of a shared conversation about their regulation and future. The work also creates encounters and exchanges within public space, creating alternative spaces outside the university setting and its neo-liberal privatization.

The artists who use public space in order to disrupt and query its corporatization are numerous and varied and span forms, from large-scale projection and interactive installation to locative media and audio artworks. Here are just a few examples:

• Film artist Jennifer West creates performance-oriented collaborative events in which members of the public participate in marking strips of celluloid to create the film experience they will then witness at a later date. The project invites participants to experience a ludic sense of time and pleasure, neither of which are controlled or codified in the ways neoliberalism seeks to make all time productive.

• New media artist Raphael Lozano Hemmer has created numerous projects situated in city squares with the explicit goal of inviting people to encounter each other face-to-face. His work employs interactive, media-based exchanges that bring experiences of intimacy with others into the public realm.

• In a slightly different vein, media artist and curator Anne Bray has leveraged the screens on the L.A. Metro bus Transit TV system for a project titled Out the Window. This project offers a showcase of videos made by local residents in place of the advertising that generally appears there. This asserts the significance of personal stories in place of commercial interests.

For the purposes of this essay, I will focus on two recent projects that resist the impact of neoliberalism and invite critical engagement with the world around us.

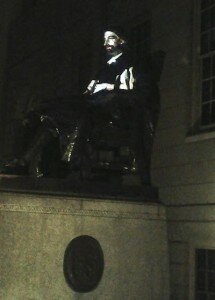

First, Krzysztof Wodiczko is known for his lengthy history creating large-scale public projections. They are designed specifically to query power, especially as it is represented in public space and embedded in both architecture and urban design. More recently, however, rather than the massive pieces for which he is known, Wodiczko has been designing more modest projections. Between April 20 and 27, 2015, he staged the John Harvard Projection designed to reimagine the “student body” of Harvard University. Using video cameras, Wodiczko interviewed a group of diverse Harvard students about their experiences as members of the Harvard community. He then precisely mapped and projected edited clips of these interviews over a public statue of John Harvard, the founder of the university, created by Daniel Chester French in 1884. The result produced a series of ghostly moving, gesturing faces and bodies layered over the sculpture. Those viewing the video could hear the voices of the students as they described their lives at Harvard.

First, Krzysztof Wodiczko is known for his lengthy history creating large-scale public projections. They are designed specifically to query power, especially as it is represented in public space and embedded in both architecture and urban design. More recently, however, rather than the massive pieces for which he is known, Wodiczko has been designing more modest projections. Between April 20 and 27, 2015, he staged the John Harvard Projection designed to reimagine the “student body” of Harvard University. Using video cameras, Wodiczko interviewed a group of diverse Harvard students about their experiences as members of the Harvard community. He then precisely mapped and projected edited clips of these interviews over a public statue of John Harvard, the founder of the university, created by Daniel Chester French in 1884. The result produced a series of ghostly moving, gesturing faces and bodies layered over the sculpture. Those viewing the video could hear the voices of the students as they described their lives at Harvard.

The piece follows a similar projection project created by the artist in 2012 when he projected images of 14 American war veterans from the Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq wars onto the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Union Square in New York City. Once again, the result was a series of almost ghostly apparitions mapped onto the statue that establish a dialogue between past and present, physical and virtual.

In both cases, the projections resisted easy recognition and appreciation. Unlike so much of the media screened in public space on myriad urban screens, Wodiczko’s projections require time and engagement in order to parse the video, to understand the images and sound, and to begin to formulate an appreciation for the layering central to the projects. In turn, viewers are invited to consider the juxtaposition of the video images and the statues that serve as their “screens.” The framing, mapping, and alignment of Wodiczko’s pieces function to establish connectivity, drawing out correspondences. At the same time, their differing materiality underscores differences that must be acknowledged and parsed for meaning. Viewers explore the dialogic relationship between the projected image and the statue, and more specifically, the ways in which the images both require the statue while simultaneously revising the statue’s symbolic meaning.

More abstractly, the projection also references contemporary experience and the ways in which so much of our lives are lived in layered spaces integrating virtual and real. These mixed reality spaces often remain unexamined; Wodiczko’s projections prompt us to consider how the spaces around us are codified, organized, and even produced within a context of what Adam Greenfield dubs “ambient informatics,” which he defines as “a state in which information is freely available at the point in space and time someone requires it” (Greenfield, 24).

A second example builds on the projected imagery in public space characteristic of the work of Wodiczko, but integrates a newer technology as well. On April 10, 2015, a massive group of protesters staged a demonstration decrying the new Spanish Citizen Security Law, which will prohibit public demonstrations near the parliament in Madrid when it is enacted in July. What made the demonstration unique was that it was composed of holographic imagery. In this way, the participants obeyed what will soon be a new law and refrained from disrupting public space with their bodies. Simultaneously, they also managed to transfer the symbolic act of protest from the deployment of physical bodies in space to the representation of those bodies; they were thus able to enact the protest anyway.

The project was sparked by Javier Urbaneja, who connected with a production company called Garlic to help with the technical logistics for the massive hologram. He also asked a group called No Somos Delito (We Are Not a Crime) to join him. The group is a consortium of organizations united in resisting the limitations imposed on public protest.

Using a website called “Holograms for Freedom,” the consortium gathered voices shouting messages that were played in conjunction with the hologram, as well as pieces of writing that they used to create protest posters that were then placed within in the video imagery. They staged and filmed a protest scene in a nearby city, being careful to create imagery that could be transferred to the street in Madrid. The organizers obtained a permit for what might have appeared to be a conventional film shoot for the Madrid event, and they placed a large screen on the street at their chosen location. On the evening of April 10, they then projected the hologram, which looked like a ghostly parade of protesters in the street, with the sounds of the many voices who had contributed to the website adding the audio.

Using a website called “Holograms for Freedom,” the consortium gathered voices shouting messages that were played in conjunction with the hologram, as well as pieces of writing that they used to create protest posters that were then placed within in the video imagery. They staged and filmed a protest scene in a nearby city, being careful to create imagery that could be transferred to the street in Madrid. The organizers obtained a permit for what might have appeared to be a conventional film shoot for the Madrid event, and they placed a large screen on the street at their chosen location. On the evening of April 10, they then projected the hologram, which looked like a ghostly parade of protesters in the street, with the sounds of the many voices who had contributed to the website adding the audio.

This project deftly stages the battle over public space by integrating the Internet and the street. The organizers understand that it is not enough to convene via online interactions; public protest and the physical gatherings staged on streets and in public squares remain essential. They visibly and symbolically defy the commodification of these spaces, and insist on the presence of a public. The hologram demonstrated both the tactical use of media to go ahead and enact the protest, but at the same time it represented even more powerfully what would be lost if the law is successfully adopted.

Through their use of projection, each of these pieces demonstrates the ways in which public space, physical objects, and digital and networked media intersect to create not the solid world, but instead a series of what Kazys Varnelis calls shifting boundaries. In a conversation with Helen Nissenbaum captured in Modulated Cities, Networked Spaces, Reconstituted Subjects, the ninth in a series of pamphlets published by the Architectural League of New York, Varnelis notes, “Instead of discrete institutions like ‘school,’ ‘work,’ ‘the family,’ and so on, we are faced with unceasingly shifting boundaries cutting across physical and social contexts” (11). He cites Gilles Deleuze and the notion of “modulations” briefly described in “Postscript on the Societies of Control” published in English in October in 1992. In the essay, Deleuze makes a distinction between societies of discipline and a new regime, the society of control. He notes that while discipline rules through enclosures and physical walls, control rules through ever-changing modulations, “like a sieve whose mesh will transmute from point to point” (Deleuze, 4). The projections in Cambridge and Madrid meet the society of control with a mechanism best suited to it, namely projections that “transmute from point to point.” The projections call into the foreground the shifting of boundaries, the mutability of spaces, and the modulations of power.

Similarly, both projects are attentive to material things. For Wodiczko, the statue is central to the artwork, and we are called upon to interrogate the ways in which this object functions before, during, and after its transformation via projection. What role does the statue play? And how does this role shift through projection? In the “Holograms for Freedom” project, the substitution of the hologram for the body queries the role of corporeality and asks what constitutes a representative body. It also signals that our gestures of agreement and our roles in participatory governing can take diverse forms across the physical and digital.

These projects are acutely aware of site; they were staged in specific physical locations to achieve specific ends. However, in their ephemerality, they reference the ways in which our city spaces are overlaid by software, which remains invisible but increasingly determines a city’s functioning. As Nigel Thrift and Shaun French note, “software is… a means of sustaining presence which we cannot access but clearly has effects, a technical substrate of unconscious meaning and activity” (Thrift and French, 312). The projections connote those layers of invisible activity, but they refuse to relinquish this space entirely to corporate interests. Instead, they inhabit it and, in the process, prompt alternative narratives for participants.

Finally, each project expands our understanding of the pedagogical possibilities in an era of corporatization and privatization. They remind us of the informal learning taking place at all times, and they call on us as faculty members to engage these points of learning often just outside the boundaries of our campuses. They invite us to imagine ways to build on this learning, and to create bridges between the university setting and public space.

Taken together, these projection-based pieces engage a public within a space of reflection; produce disruptive or alternative narratives within that space, specifically through a form of projection and layering; and make legible what too often remains invisible. They also provide an infrastructure for the civic imagination, a term that Henry Jenkins has developed to describe the design of images that can be deployed across a variety of media forms to spark participation and a vision for the future. These examples can be productive for those of us within education, especially for those of us committed to helping students witness and counter the corporatization of American higher education.

Works Cited

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. New York: Verso, 2012. Print.

Deleuze, Gilles. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” October, Vol. 59 (Winter, 1992), pp. 3-7.

Gamber-Thompson, Liana. “Hot Spot Overview: By Any Media Necessary.” March 26, 2014. Blog post.

Goldfarb, Brian. Visual Pedagogy: Media Cultures in and beyond the Classroom. Duke University Press Books, 2002. Print.

Greenfield, Adam. Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing. Berkeley, CA: New Riders Publishing, 2006. Print.

Helguera, Pablo. Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook. New York, NY: Jorge Pinto Books Inc., 2011. Print.

Nissenbaum, Helen and Kazys Varnelis, Situated Technologies Pamphlets 9: Modulated Cities: Networked Spaces, Reconstituted Subjects, New York: New York Architectural League, Spring 2012.

Raley, Rita. Tactical Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. Print.

Thompson, Nato, ed. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 2012. Print.

Thrift, Nigel and Shaun French, “The Automatic Production of Space,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 27, No. 3 (2002), pp. 309-335.

Holly Willis is a faculty member in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, where she serves as the Chair of the Media Arts + Practice Division. She is the co-founder of Filmmaker Magazine, dedicated to independent filmmaking; she is the editor of The New Ecology of Things, a book about ubiquitous computing; and she is the author of New Digital Cinema: Reinventing the Moving Image, which chronicles the advent of digital filmmaking tools and their impact on contemporary media practices. She publishes a column on contemporary film schools for Filmmaker Magazine, and writes frequently about experimental film, video, design, and new media, as well as trends in higher education and new directions in teaching and learning.