Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Vol. 2(2) Spring 2014

Maurizio Viano

Wellesley College

Cinema Journal Teaching Dossier

Vol. 2(2) Spring 2014

Maurizio Viano

Wellesley College

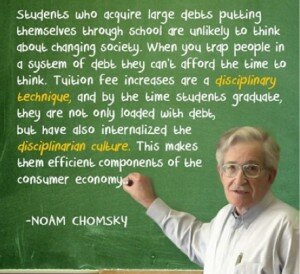

The paradox in the images evoked by the first two bullets in this dossier’s call for proposals is so striking as to bear scrutiny: on the one hand, the “critical thinking citizen,” ideally formed by our teaching; and on the other, the “understandably anxious” parents and students to be persuaded by the case (sale pitch) we make for the value of a liberal arts education. In the paradoxical haze of this predicament, are we allowed to have a dream—the dream of becoming “understandably critical,” aware of this:

Indeed, becoming “understandably critical” would mean seeing through the fog of all democratic, republican and neocon smokescreens that in the past 35 years have occluded the common denominator which has led the globe and U.S. higher education to where we presently are: neoliberalism.

Indeed, becoming “understandably critical” would mean seeing through the fog of all democratic, republican and neocon smokescreens that in the past 35 years have occluded the common denominator which has led the globe and U.S. higher education to where we presently are: neoliberalism.

What is Neoliberalism?

In a 2009 New York Times column, Stanley Fish reports “reading essays in which the adjective neoliberal was routinely invoked as an accusation” but admits he “had only a sketchy notion of what was intended by it.” Five years later, in the wake of a worldwide economic meltdown, confusion as to neoliberalism’s definition and basic effects is no longer possible: “Neoliberalism is the defining political economic paradigm of our time — it refers to the policies and processes whereby a relative handful of private interests are permitted to control as much as possible of social life in order to maximize their personal profit. Associated initially with Reagan and Thatcher, for the past two decades neoliberalism has been the dominant global political economic trend adopted by political parties of the center and much of the traditional left as well as the right” (McChesney, 7). The steadily increasing bibliography on neoliberalism’s impact on art (Jump Cut 53), the so-called “creative industries” (ibid.) and, most importantly, higher education (Jump Cut 55 and Giroux ) is a sign that we are at last connecting the dots. According to Fish, “the ‘historical legacy’ of the university conceived ‘as a crucial public sphere’ has given way to a university that now narrates itself in terms that are more instrumental, commercial and practical.” Here, let us chart neoliberalism’s ripple effects on cinema and media studies specifically.

Decrease in Majors

The number of students who might consider majoring in cinema and media studies but choose differently is rising. A case in point is to be found at Wellesley College, where the Cinema and Media Studies program (CAMS) has to face the crushing competition of an interdepartmental major named Media Arts and Sciences (MAS). The latter’s curriculum emphasizes marketable assets such as programming for networked environments and web-connected database architectures. CAMS cross-lists quite a few MAS courses (e.g. digital imaging and design), but it is not enough. Students and parents deem the study of cinema “impractical” while foundation courses in computer science ensure that the MAS major thrives.

Populism and Quantitative Reasoning

Just as a film’s value is ubiquitously measured in terms of box office figures, students valorize only the study of things sanctioned by the market. Fomented by the postmodern bias against the alleged elitism of film theory and art cinema, students would rather learn about popular cinema alone rather than accept our pedagogic plea that college is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to expand their horizons and learn about other modes of filmmaking and media production. As the boundary between knowledge and fandom is eroded, even our majors’ resistance against watching foreign films can be chalked up to their populist fixation on a quantifiable market for which they dream of concocting the breakthrough pilot.

The Ideology of the Upgrade

The pervasive ideology of the upgrade hugely impacts our fields by creating the impression that only today’s media forms and post-CGI films are worth studying. Through reminders forcing themselves on our screen, the interpellation of the upgrade not only incessantly produces ‘natural’ needs and hierarchies, but also downgrades all that is historical—effectively defusing history’s relevance. Walter Benjamin’s hopeful dialectical image emerging from the conflation of historical vision and critical present is less likely to flash up on media commodities whose temporality is that of fashion’s apparel and whose logic is grounded in the ineluctability of scientific progress.

The Divide and Conquer of Identity Politics

The naturalization of capitalism has not only wiped potential alternatives from the radar; it has also eclipsed all rethinking of class in the global North’s knowledge economy, indirectly privileging the “easy” antagonism of identity politics. The exclusive focus on immediately visible fractures and ‘natural’ alliances occludes the potential of a common struggle against an enemy whose visibility can only emerge by connecting the dots of political economy. Furthermore, just as it over-determines taste, neoliberal ideology influences the students’ perception of a film’s politics. Form is ignored; narrative and plot are all that matters. In fact, the ongoing “Victim Olympics” sweeping campuses and determining students’ appreciation of films has redefined what politics is.

Dark Night of the Soul

Neoliberalism forces all humanities majors and professors to measure their worth against the market. On the Forbes‘ website, Peter Cohan suggests that the solution to the education crisis “could be as simple as eliminating the departments that offer majors that employers do not value,” concluding: “One thing is clear, academia’s effort to preserve its special exemption from the laws of economics is becoming too burdensome for many students, parents, and lenders to bear.” Put under pressure to account of our curriculum’s exchange-value, we risk internalizing the gaze of the “Big Other” (the market). This enforced ego fragility is compounded with the stress that new work patterns impose on the cognitariat, the labor force in the knowledge economy of which we are part and which our education produces. Under the 24/7 regime of media connectivity, systemic ADHD and mental health problems become the norm. In keeping with the prevailing scientism, these issues are entirely biologized, with little attempt at understanding the role that cultural, economic and socio-political factors might play in their formation. Unequipped with the critical tools to understand the psycho-politics of what Italian philosopher Franco Berardi calls “the soul at work,” our students are vulnerable to the plethora of mental symptoms against which an “understandably critical” mind is an antidote.

Two Ideas From Without

A 2012 Harvard College report identifies problems with the teaching of the humanities in elite colleges. Of interest here is the report’s acute perception that faculty overspecialization has lead to an excessive and dangerous narrowness in the scope of undergraduate courses. A possible way out might “profitably involve reaffirmation of the generalist tradition of undergraduate teaching” (30). Insofar as the generalist combines many disciplinary interests in her/his person, reviving the generalist tradition also means valorizing Cinema and Media Studies, the interdisciplinary subject par excellence. In small liberal arts colleges, with the humanities increasingly less patronized by students, we have the chance, indeed the duty, of showing how many tangents and ramifications film studies can produce. Instead of plumbing the depths of a specialist approach, our courses could emphasize the links between cinema/media texts and their many contexts. Insofar as the generalist approach enables an understanding of how the whole and its parts fit together, this pars pro toto teaching would encourage the absorption of the dialectical method by the student.

Toby Miller states that there are two humanities in the United States. “Humanities One resides in fancy private universities” and colleges and “tends to determine how the sector is discussed in public” (1). The second humanities, instead, is that of “state schools which focus more on job prospects.” Arguing that “the distinction between them […] places literature, history and philosophy on one side (Humanities One) and communication and media studies on the other (Humanities Two)” (2), Miller proposes to dynamite this opposition. Critical of the neoliberal complicity between creative industries (e.g. video-games) and the military industrial complex, and eager to expose corporate Siliwood (the synergistic investments and profits of Silicon Valley and Hollywood), Miller argues that the humanities must not forsake their chance to sit at the table where valuable knowledge is produced and debated. This is not achieved by aping the sciences and their methods, but by forging ahead in what he calls Humanities Three: “The two humanities must merge” under the aegis of media and cultural studies, the only inter-disciplines capable of ensuring “a blend of political economy, textual analysis, ethnography, and environmental studies such that students learn the materiality of how meaning is made, conveyed and discarded” (105).

Two Ideas From Within

Embracing the generalist approach, our two-semester film history requirement is abandoning the paranoid duty of chronological exposition and exhaustive coverage. We have moved towards a study of relevant constellations (e.g. Modernity/Modernism; Animation/Movement; Laughter) that combines reading theory, watching exemplary films, and asking the class to envision contextual and inter-textual bridges. The whole is done in a cross-eyed fashion—one eye trained on the story of film, the other on the generalist’s need—seeking links with other arts/media/disciplines. This course also minimizes academic essay writing and asks students to produce knowledge through videographic essays. Precisely because we are “uniquely positioned” between the pre-professional and traditional humanities, stepping up the production component in all theory and history courses constitutes a tectonic shift in our discipline, one of the best ways to honor the “third way” proposed by Miller.

When hiring a CAMS faculty last year, we chose a new media theorist whose expertise in sound studies expands the notion of media beyond the screen-based. His new media courses straddle the philosophical reflection of Humanities One with the heuristic pragmatism of Humanities Two. In fact, in their multifaceted nature, these courses jut out towards the Social Sciences and intersect Computer Science as well (while adding the critical-political component often missing in them). More importantly, they all implement that integration of theory and practice we have established as our distinctive trait. For example, in my colleague’s course on the Internet, the reading of theoretical texts is accompanied by small experiments aimed at demonstrating data flow from one machine to the other, thus enabling students to begin speaking and typing computer protocols. If the neoliberal ethos asks you to use a computer as a consumer, his teaching counters such ideology by offering students the comprehension of how things work. Connecting to a web server and experimenting with what is going on behind the scenes, students combine consumption with production, thereby upsetting the dichotomy. In his words, “it is something like opening the black box.”

Locating and opening the black box gives a critical spin to the integration of theory and production,. Indeed, such integration might make our unique position in the curriculum central to education in the small liberal arts college. If wisely conjugated with a generalist approach and the digital articulation of theory and practice, a critical audiovisual literacy could aspire to become the “qualitative reasoning requirement” that some of us at Wellesley College feel should provide a counterweight to the quantitative reasoning requirement that was instituted some twenty years ago and that sealed the rising impact of a market driven knowledge.

Works Cited

Berardi, Franco. The Soul at Work: From Alienation to Autonomy. New York, Semiotext(e), 2009.

Cohan, Peter. “To Boost Post-College Prospects, Cut Humanities Departments,” Forbes.com, 5/29/2012, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://www.forbes.com/sites/petercohan/2012/05/29/to-boost-post-college-prospects-cut-humanities-departments/

Fish, Stanley, Neoliberalism and Higher Education. The New York Times, March 8, 2009, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/03/08/neoliberalism-and-higher-education/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0

Giroux, Henry. “Neoliberalism, Democracy and the University as a Public Sphere.” truth-out.org, April 22, 2014, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://www.truth-out.org/opinion/item/23156-henry-a-giroux-neoliberalism-democracy-and-the-university-as-a-public-sphere

Hess, John, Kleinhans, Chuck, and Lesage, Julia. “The war on/in higher education.” Jump Cut, No. 55, Fall 2013, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://www.ejumpcut.org/currentissue/LastWordNeolibAttackEdn/index.html

Kapur, Jyotsna, and Wagner Keith, eds. Neoliberalism and Global Cinema: Capital, Culture, and Marxist Critique. London and New York: Routledge, 2013.

Kapur, Jyotsna. “Capital Limits on Creativity: Neoliberalism and its Uses of Art.” Jump Cut, No. 53, Summer 2011, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc53.2011/KapurCreativeIndus/index.html

Kleinhans, Chuck. “‘Creative Industries,’ Neoliberal Fantasies, and the Cold, Hard Facts of Global Recession: Some Basic Lessons.” Jump Cut, No. 53, Summer 2011, accessed May 19, 2014.

http://www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc53.2011/kleinhans-creatIndus/index.html

McChesney, Robert W. “Introduction,” in Noam Chomsky, Profit over People: Neoliberalism and Global Order. New York: Seven Stories Press, 1999.

Miller, Toby. Blow Up the Humanities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

Working Group. The Teaching of the Arts and Humanities at Harvard College: Mapping the Future, 2013, accessed May 19, 2014. http://harvardmagazine.com/sites/default/files/Mapping%20the%20Future%20of%20the%20Humanities.pdf