JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (3)

JCMS Teaching Dossier Vol 5 (3)

Not Another Brick in the Wall: The Audiovisual Essay and Radical Pedagogy

Catherine Fowler

“You are in darkness. On the small rectangle of the editing table, imagery goes by. Slightly clenched on the control, your hand feels the image. It feels, it knows, it thinks it can control the image.” —Bellour, 2012 [1990], 12

The early experience of close textual analysis as described here by Raymond Bellour, seated at the Steenbeck, is replicated in contemporary videographic exercises, which will also begin with the attempt to control the image. Rather than completed audiovisual essays it is exercises with video editing in the classroom that concerns me here: videographic exercises as method, process and critical matter. For students in my French new wave class, the instruction not simply to feel and control the image but to re-use and re-make it was freeing. It produced a powerful shift in their thinking. More than that it changed the dynamics of the classroom, transforming it into a space full of the potential for a kind of radical pedagogy.

All images © Catherine Fowler.

A common goal of “radical pedagogy” is to change consciousness. Take Paolo Freire’s infamous practice, which he articulates as a “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (Freire, 1970). For Cornell West: “Freire’s project of democratic dialogue is attuned to the concrete operations of power (in and out of the classroom) and grounded in the painful yet empowering process of conscientization” (West, 1993, xiii). By “conscientization” West is referring to moments in which a combination of social theory, powerful polemics and political praxis brings about a shift in perspective. For Freire what matters most is that such a shift is co-created between teachers and students via classroom strategies such as problem-posing, cooperation, and dialogics. Seen in light of Freire’s teaching, radical pedagogy clearly has ambitions to change minds and hearts, social conditions, and political ideologies, as such we might well struggle to easily identify the radical pedagogy of videographic exercises and video essays. Will they address racial, class, and ethnic oppressions? Possibly. Have they caused a revolution? We don’t yet know. Reports from those who teach video essays rarely make such bold claims, instead their advocacy is far gentler. Chiara Grizzaffi has noted that videographic exercises take students beyond surface meanings, allowing them also to focus on a “didactic purpose” (2014). Christian Keathley (2014) suggests that the aesthetic choices students make are analogous to rhetorical choices. While for Leah Shafer (2013) something about editing, remixing, annotating, and combining video and sound from archival videos demystifies the material.

It would be hard to argue that my classroom resembles Freire’s entirely—clearly my students are from the western privileged class—yet even so the specificities of the context mean that inhibiting power relations are present. Language learning is in decline in New Zealand and art house films are exhibited only in a limited way – largely for 3 weeks during the International Film Festival. Hence, when I teach my French new wave course to New Zealand based students I have barriers to overcome regarding the foreignness of the films. In my classroom I have always prioritised dialogue and discussion, in an attempt to overcome the unequal cultural “knowledge” that existed between myself (French speaker and teacher of French cinema for over two decades) and my students (of whom only a minority may have studied French language or know a little French history). Similarly, anyone who has taught the French new wave will know how easily students can be hooked in by the Parisian hipness of A bout de souffle (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960), Les Cousins (Claude Chabrol, 1958) or Paris nous appartient (Jacques Rivette, 1960), the affecting authenticity of Les Quatre Cents Coups the eclectic experiments of Chronique d’un été (Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin, 1960), Hiroshima Mon Amour (Alain Resnais, 1959) and La Jetée (Chris Marker, 1962) and the feminist frisson of Cléo de 5 à 7 (Agnès Varda, 1962). In other words, both the pedagogic strategies I employ and the films themselves have the potential to “convert” students. All the same, introducing videographic exercises into the classroom has brought a powerful shift in attitudes. To explain this shift I’ll provide an example.

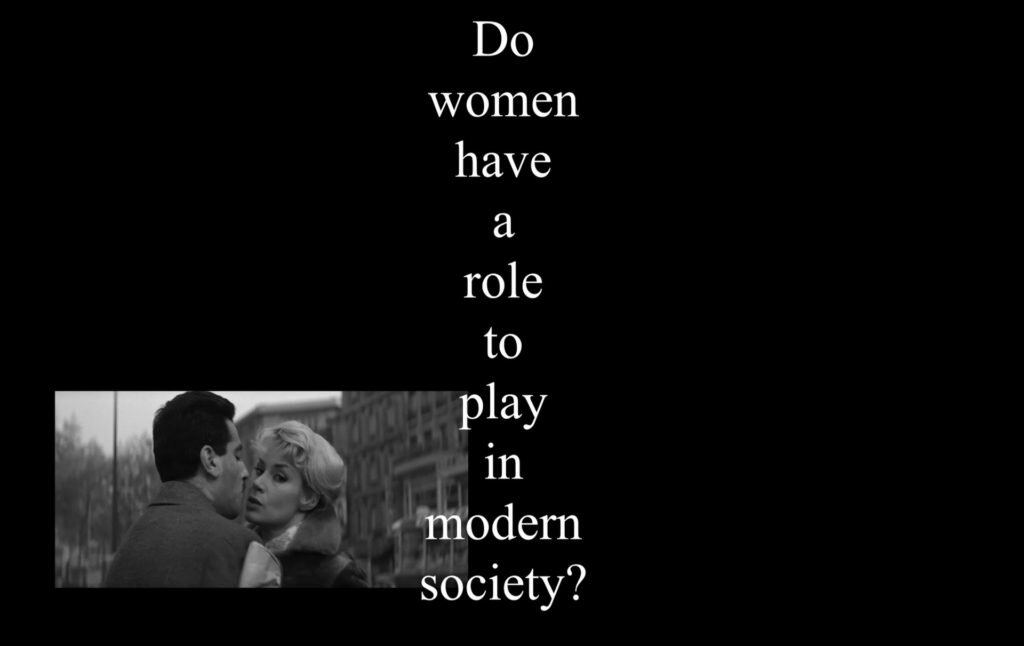

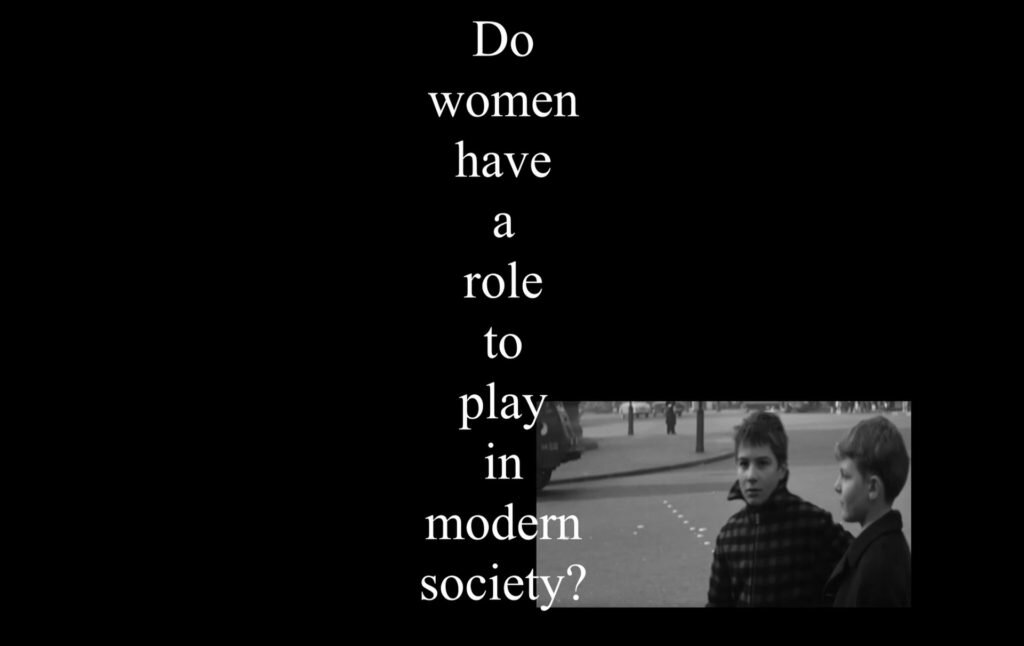

Students were provided with a clip of audio from A bout de souffle. The file contained a moment from an interview that the main female character, Patricia, (played by Jean Seberg), conducts with a novelist (played by real-life director Jean-Pierre Melville). Patricia asks the question “Do you think women have a role to play in modern society?” The objective of the one-minute exercise was to try out the technique of comparison provided by multiple screens, and to use the question to interrogate how women are represented in any French new wave films. Figures 1 and 2 show screen grabs from one resulting video.

Figure 1

Figure 2

As you can see, the student decided to have the question fade up in the centre of the frame in order to highlight the comparative element. After a few seconds the two clips appeared, one of Michel (Jean-Paul Belmondo) looking apparently out of frame, the other of Patricia, absorbed in observing herself in a mirror. Standing side on to the mirror, Patricia pulls back her coat and places her hand on her belly, then looks down at it. The student’s video cuts at this point, but in the film in the following scene Patricia confirms what we think we’ve seen: she thinks she is pregnant.

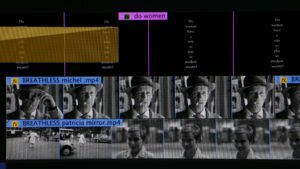

The video described above came together in the first hour of the class, this was followed by the presentation of all videos and then group discussion. Referring to their choice of clips for the video described above, the student spoke of becoming aware that the question of the role of women is relatively buried in a number of new wave films. In A bout de souffle Patricia’s pregnancy is glossed over in the film, and we never find out if she actually was pregnant. The student’s intention was to use the dual screen format like a shot reverse shot, and indeed it does appear as if Michel is watching Patricia as she has a candid moment alone. Watching this video inspired other students to follow the same idea, resulting, for example, in video two which adopts the same configuration, with the question dividing the two screens, but features a number of short shots from Les quatre cents coups. (See Figures 3–8.)

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

Again, the scenes chosen attend to a blink-and-you-miss-it moment in which female desire is fleetingly centre frame. The twelve-year-old Antoine (Jean-Pierre Léaud) has bunked off school to hang out with his friend in the city. Crossing a busy road he glimpses sight of his mother, but she is in a tryst with an unknown man. Mother and son catch sight of each other, but then quickly look away, both caught in acts of deception and therefore unwitting keepers of each others’ secrets.

The combination of sitting alone in front of films, followed by cutting them up and making something new, then re-shaping ideas together, created a highly animated classroom. In case it sounds like I’m overstating what may seem to some like regular teaching strategies, I probably need to pin down the source of animation. Doing so should bring us back to our starting point, with radical pedagogy. The teaching context for this videographic exercise was that of a seminar/tutorial: a space, then, designed for debate and discussion. Close textual analysis of films, discussion of reading materials, exercises that evaluate both and organise responses in the form of tables and statements; these are all part of such a teaching context. The videographic exercise elicited a comparative level of discussion, debate, analysis and discovery, yet what it added was a sense that the text is open to everyone in the room, in spite of the different knowledge levels that each brings. The act of importing short scenes from A bout de souffle or Les quatre cents coups may appear as the equivalent of Bellour’s attempt to control the image, as he runs it back and forth through the Steenbeck, but in fact, when this assemblage is part of a videographic exercise, it places the notion of control—whether the original authorial control of the film or the teacher’s control of the classroom—under scrutiny.

A cross-over with Freire’s radical pedagogy is apparent once we reflect upon the ‘coming out’ of the classroom in discussions of videographic exercises. Whereas it’s fair to say that for a long time the question of how we teach was reserved for those corridor conversations that happen in between panels at conferences, there has been an encouraging rise in discussions of what can, should and does go on in the classroom, with this journal’s teaching dossier being one shining example. And what emerges from the scholarship produced around teaching video essays is a renewed sense of pedagogy. To Freire’s notion we can add a discussion that is closer to our discipline. In the mid-1980s Screen re-visited the notion of pedagogy. Attempting to finesse this woolly notion David Lusted distinguished pedagogy from teaching, arguing that it “draws attention to the process through which knowledge is produced” (Lusted, 1986 [original emphasis]). What unites Freire’s and Lusted’s positions is an interest in the classroom as a pedagogical space where teacher and student come together to test, protest, and contest what is understood as knowledge.

We may not yet have proof that requiring our students to make video essays as assessment tasks brings about a change in individual consciousness, but there is evidence that they are changing film and media teaching and learning in ways that suggest a renewed consciousness of pedagogy is emerging. In short, videographic exercises have reinforced the sense that, as Lusted puts it: “knowledge is not the matter that is offered so much as the matter that is understood” (Ibid., 4). In other words, knowledge does not pre-exist the teaching space, instead in the teaching space student and teacher work together. Thinking of knowledge as a kind of matter, or as having a materiality, recognises the micro-moments of learning that are hard to vocalise and quantify and that escape assessment regimes. By feeling, controlling, re-using, and re-making films, perhaps we can change students’ relationship to learning as well as our relationship to teaching.

References

Bellour, Raymond. Between-the-Images. Translated by Allyn Hardwick. Zurich, Dijon: JRP Ringier, Les presses du reel, 2012.

Freire, Paolo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. The Continuum Publishing Company,1970.

Grizzaffi, Chiara. ‘Between Freedom and Constraints: What I Learned from Teaching Video Essays.’ The Cine-files Fall, no. 7 (2014).

Hall, Macie. ‘Bringing Digital Humanities into the Classroom’. Blog post April 3, 2015. http://ii.library.jhu.edu/2015/04/03/bringing-digital-humanities-into-the-classroom/

Keathley, Christian. “Teaching Videographic Film Studies.” The Cine-Files Fall, no. 7 (2014).

Lusted, David. ‘Why Pedagogy?’. Screen 27, no. 5 (1986): 2-16.

Shafer, Leah. ‘The Video Essay as Curatorial Enterprise’. Cinema Journal 1, no. 2 (Summer 2013).

Wallis, Richard and David Buckingham. ‘Media Literacy: the UK’s undead cultural policy’. International Journal of Cultural Policy. (2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1229314

West, Cornell. ‘Preface’. In Paolo Freire – a Critical Encounter, edited by Peter, Leonard McLaren, Peter, London and New York: Routledge, 1993: xiii-xvi.

Catherine Fowler is an Associate Professor in Film at Otago University, New Zealand. Her research focuses on the art and film axis of influence, feminism and film and European cinemas. She has taught audiovisual essay workshops to high school students. With Claire Perkins and Andrea Rassell she has made an audiovisual essay focusing on the long take in cinema which was published in [in]Transitions journal.

Promise of online teaching for English tutors online

The research contains many case studies that investigate how universities and colleges utilized creative teaching and learning strategies throughout the epidemic, as well as how their students responded. As an example: Using pre- and post-tutoring exams and surveys, the researchers discovered that studying with an English tutor online increased students' performance on standardized examinations … Continue reading